Co-design for Shared Energy Communities

Timeframe: 5 Months

Tools: Pen & paper prototyping, Figma

My Role: UX Designer and Workshop Facilitator

Project Overview

This was a 5-month participatory design project focused on exploring how communities can coordinate and manage shared solar energy more effectively. I helped facilitate a series of co-design workshops with primary school students in a London borough. Together, we explored ways to support energy fairness, awareness, and collaboration through creative app concepts.

The work here has been published in the International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2025.100802.

Problem Statement

In the context of increasing energy demands and the push toward renewable sources, energy communities, which are groups that share access to solar energy, are emerging as a viable solution. However, while the infrastructure for generating solar energy may be in place, the coordination of its use remains a major challenge.

This project focused on one such borough in London where solar panels were installed, but questions remained around how neighbours could collaboratively use this shared energy more effectively. Unlike traditional individual consumption models, shared energy systems require cooperation, communication, and sometimes compromise. This brings up questions like:

Who gets access to the energy at peak generation times?

How do we decide between needs like lighting up a neon sign versus powering a medical device?

Can we design systems that are fair, transparent, and motivating?

We also explored the potential role of AI in these systems. Rather than acting as a black-box decision-maker, can AI support human values like fairness, inclusivity, and transparency? Can it mediate conversations, facilitate sharing, or help users form habits that align with community goals?

Design Process

Empathize

->

Define

->

Ideate

<->

Prototype

<->

Test

...........

Empathize -> Define -> Ideate <-> Prototype <-> Test ...........

Empathize

To kick off the design process, we visited a local primary school in London to run a series of co-design workshops with students aged 12-14. Our goal was to help them connect with the idea of shared solar energy in their communities. Through guided activities and storytelling, we encouraged them to think critically about how energy is used, who needs it most, and how decisions around it can affect others.

Situated Awareness

Rather than treating the students purely as research subjects, we aimed to immerse them in the real-world context of shared energy coordination and empower them to become designers themselves. To do this, we crafted storytelling scenarios that helped them relate to the challenges of energy fairness and limited resources.

We introduced them to two fictional characters:

Muhammad, who uses solar energy to power a decorative neon sign of his name, and

Hamreet, who relies on it for a critical medical device.

DEfine <-> Ideate <-> Test

Goals

We worked together to identify key goals for an energy-sharing app:

Save energy

Learn about energy

Share energy fairly

Communicate with neighbours

IDEating

To move from empathy to action, we facilitated a hands-on design workshop with students, guiding them through a creative process to generate and refine their own app ideas around shared solar energy use.

We began by dividing the participants into four groups of 2–6 students. The goal was to encourage collaboration, imagination, and critical thinking in how they approached energy fairness, coordination, and technology.

Crazy 8’s Warmup

To help spark creativity and loosen up any hesitation, we introduced the Crazy 8s activity, a rapid ideation exercise where students sketched eight distinct app ideas in eight minutes. This helped them generate a variety of directions quickly and pushed them to think beyond their first idea.

From Sketch to Screen

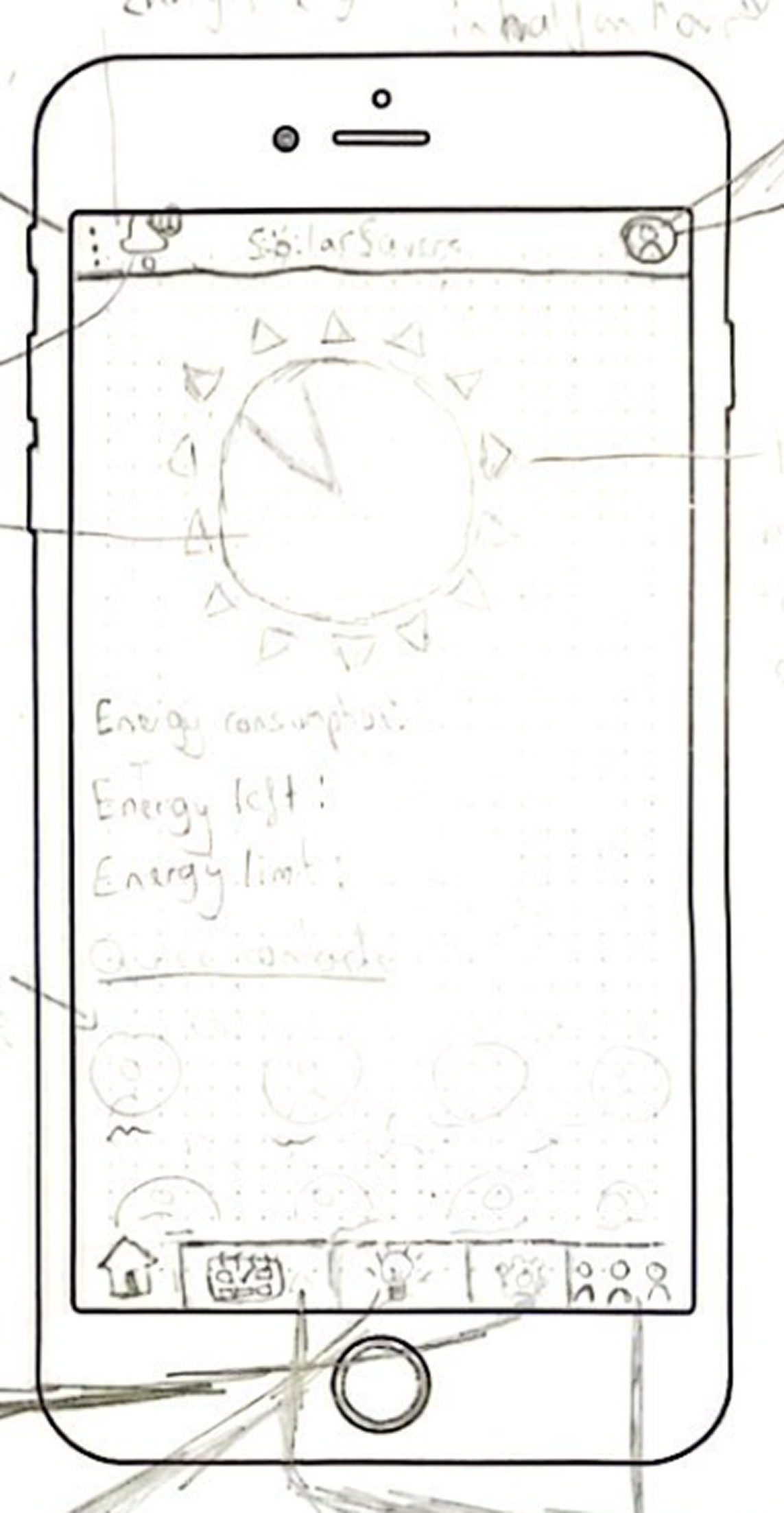

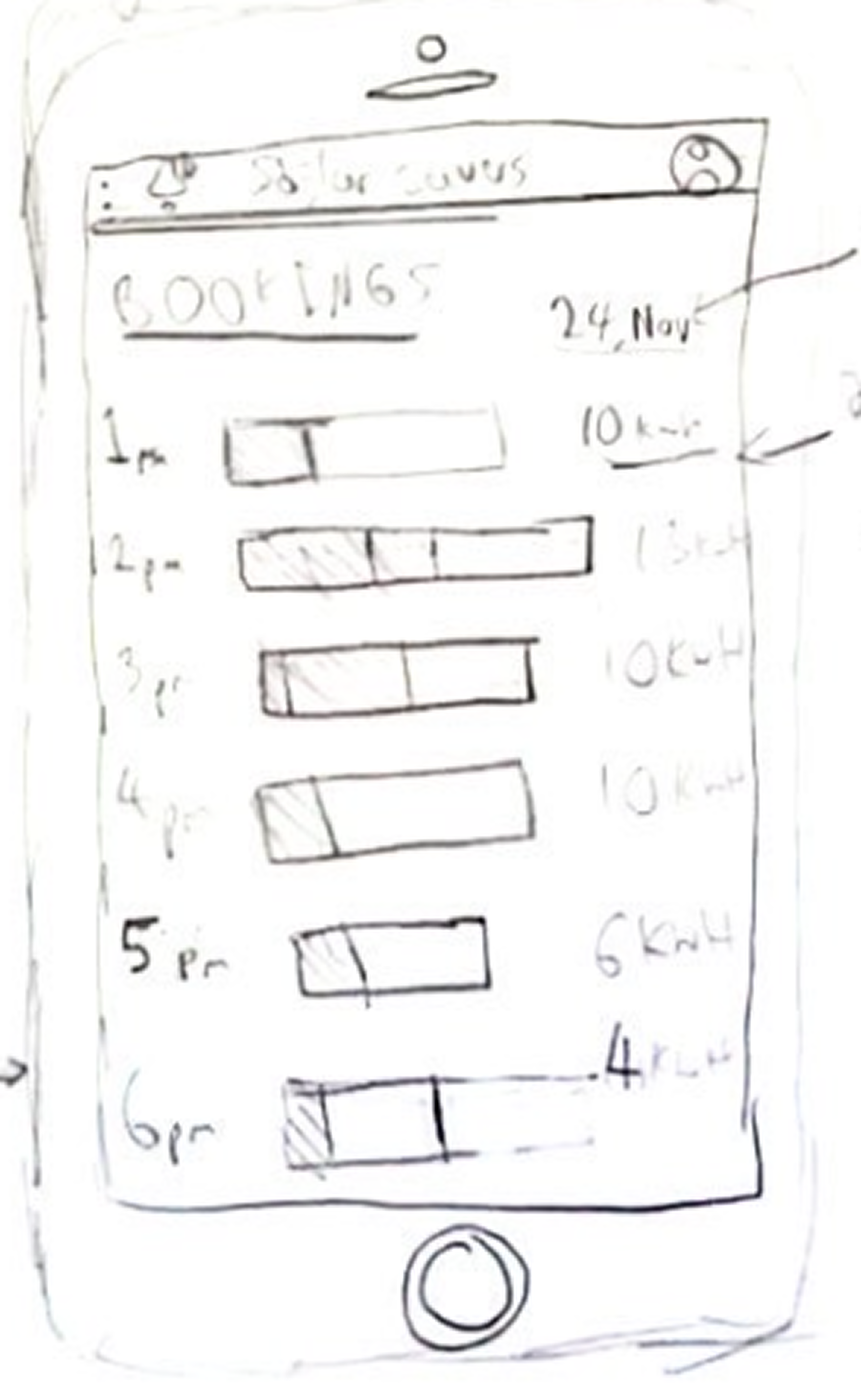

Each group then selected their favourite idea from their Crazy 8s sketches and worked together to iterate on it. They created more detailed wireframes, considered functionality, and discussed user flows.

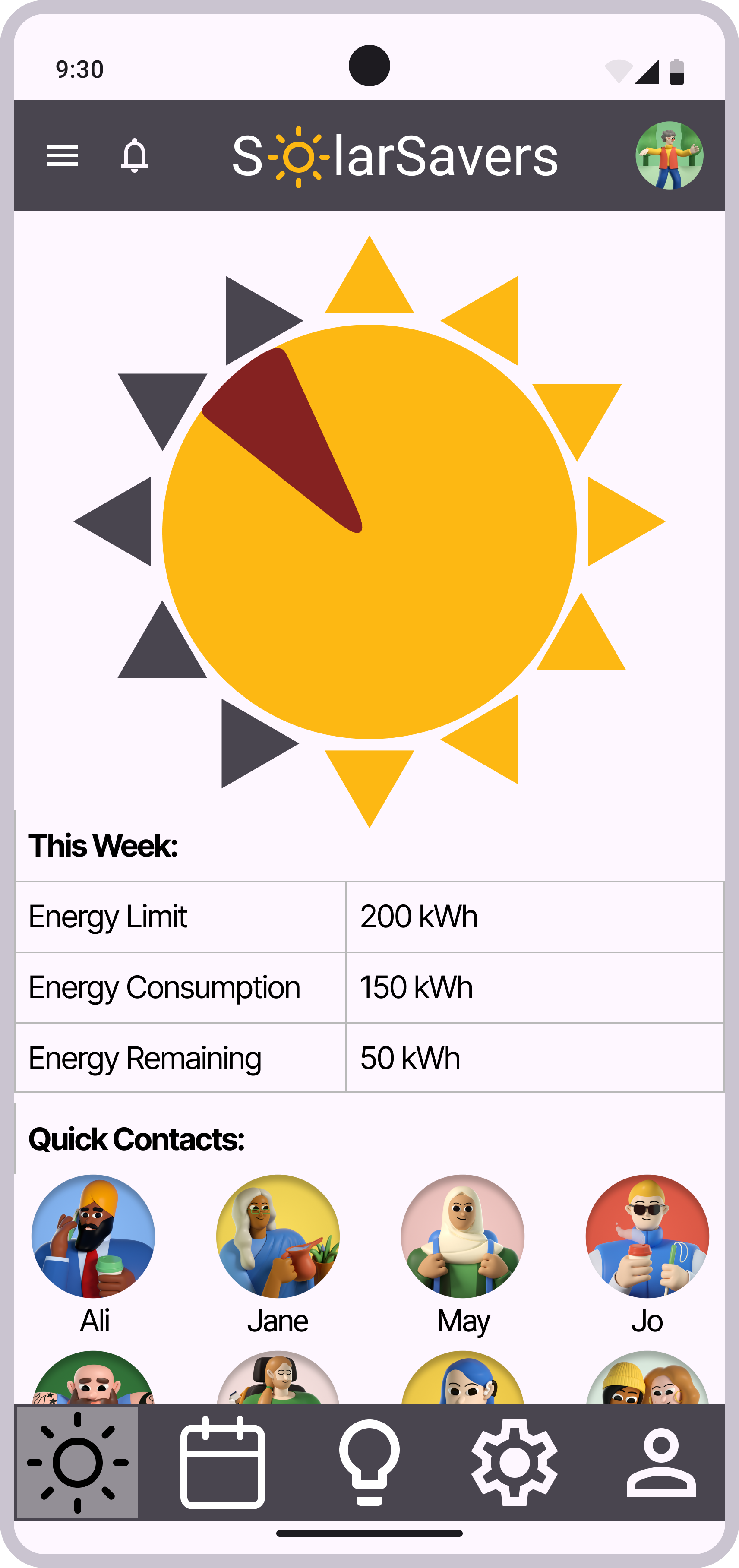

Throughout this phase, my role was to facilitate, encourage idea development, and translate their sketches into clearer digital iterations, without imposing my creative direction. My goal was to retain the students’ core intentions and amplify their design voices through clearer visuals.

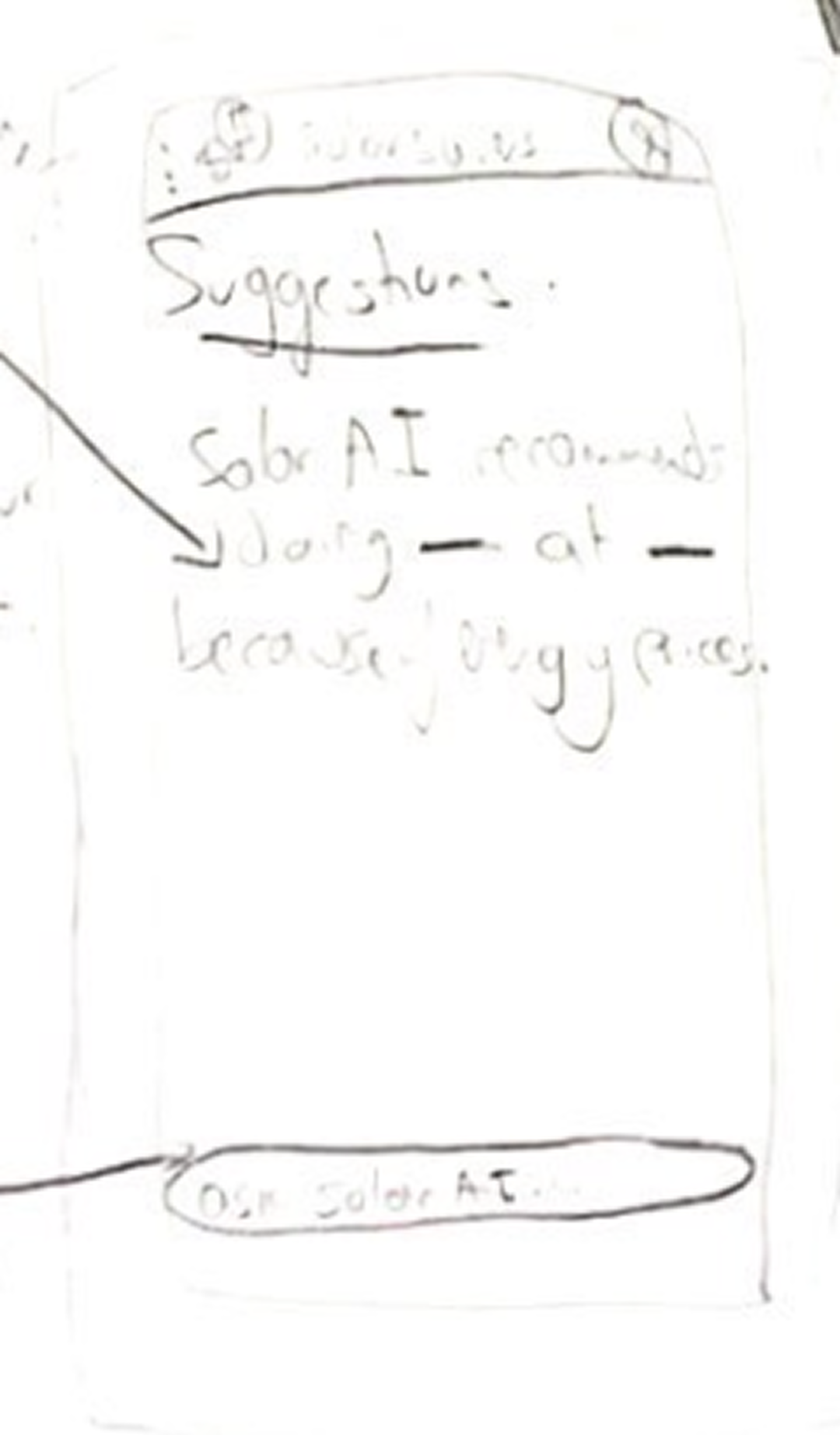

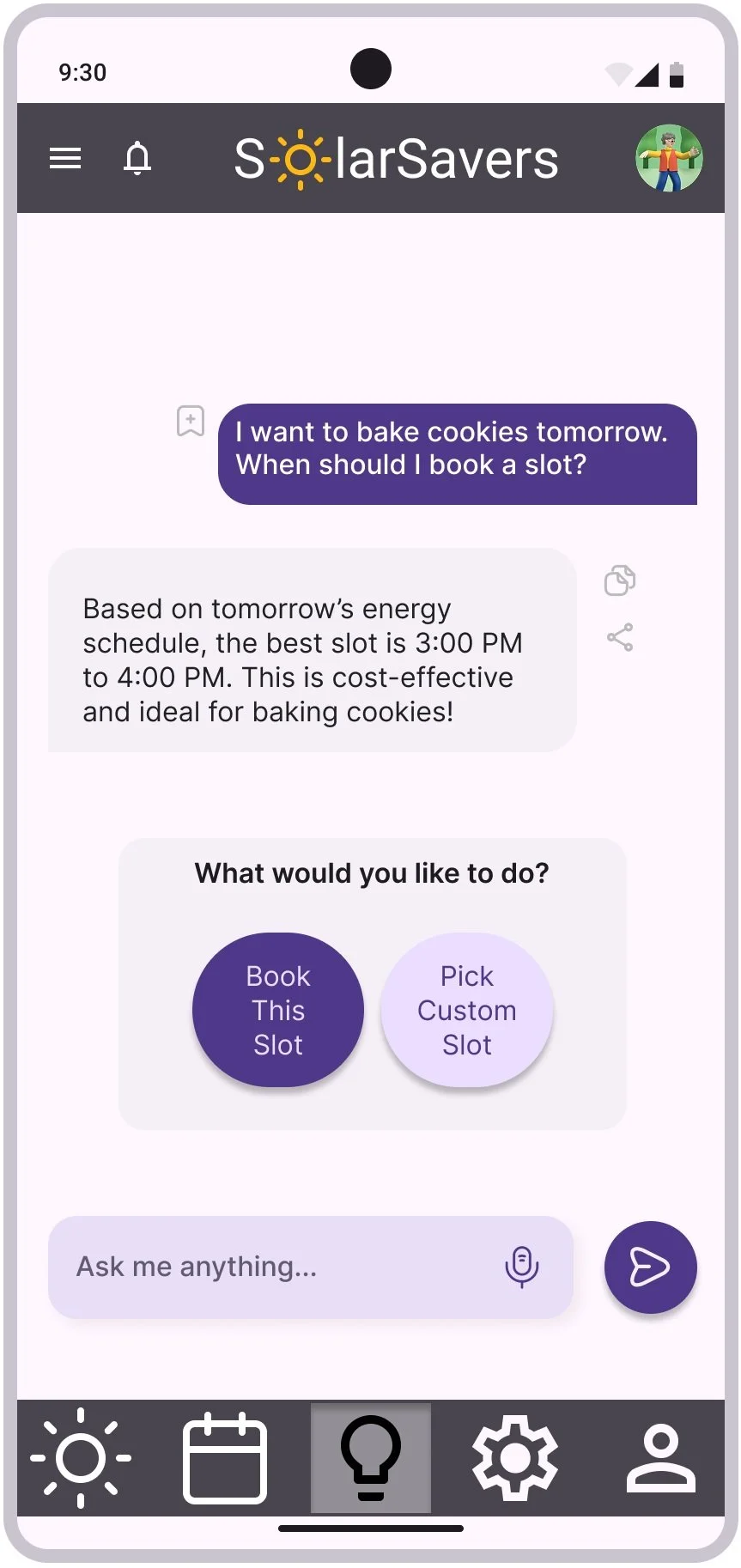

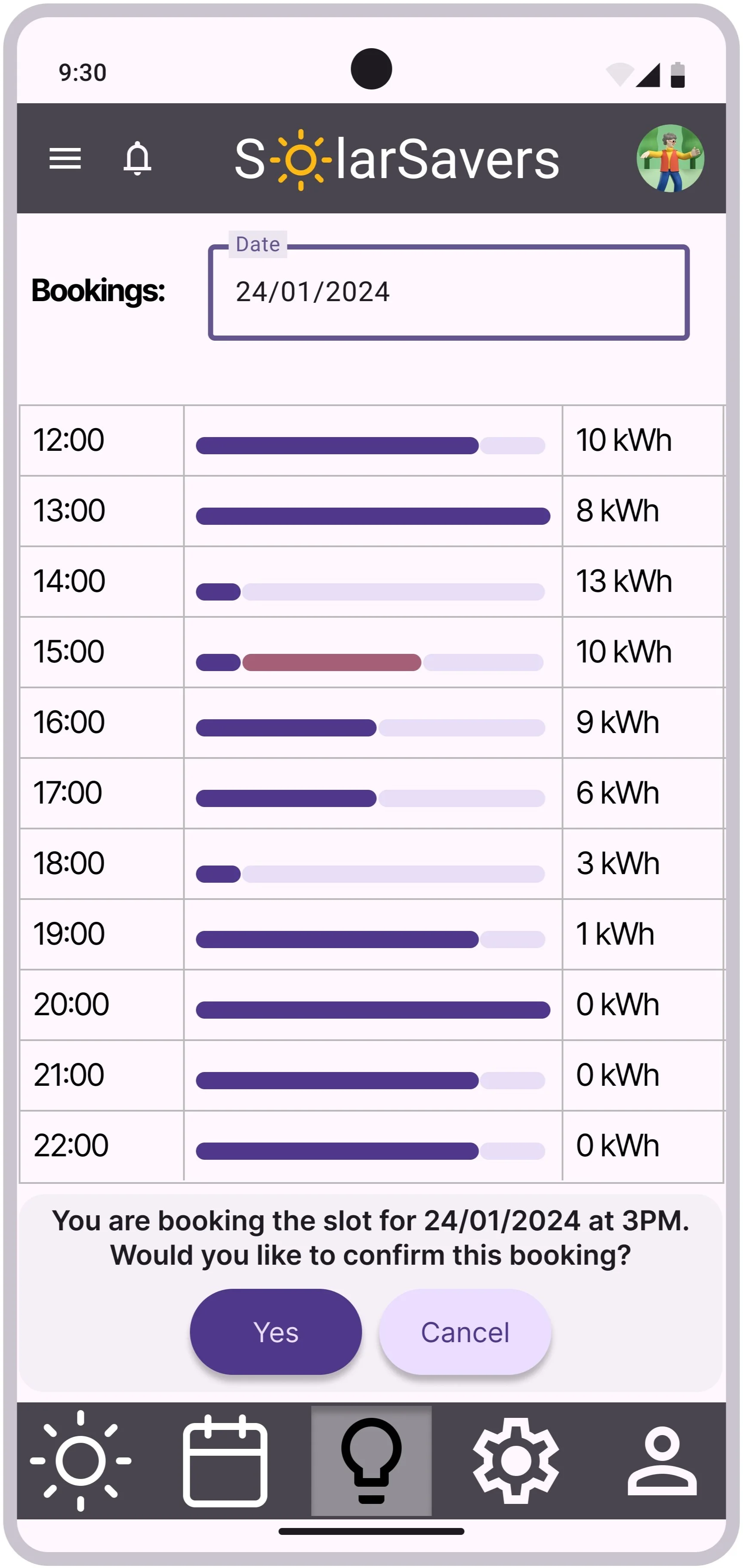

Group 1: SolarSavers

This group introduced the idea of booking time slots for energy usage, allowing fair access to a limited energy pool.

They imagined AI as a motivator, offering awards like “Best Neighbour” to encourage responsible behaviour as well as an assistant in providing suitable information to improve booking efficiency.

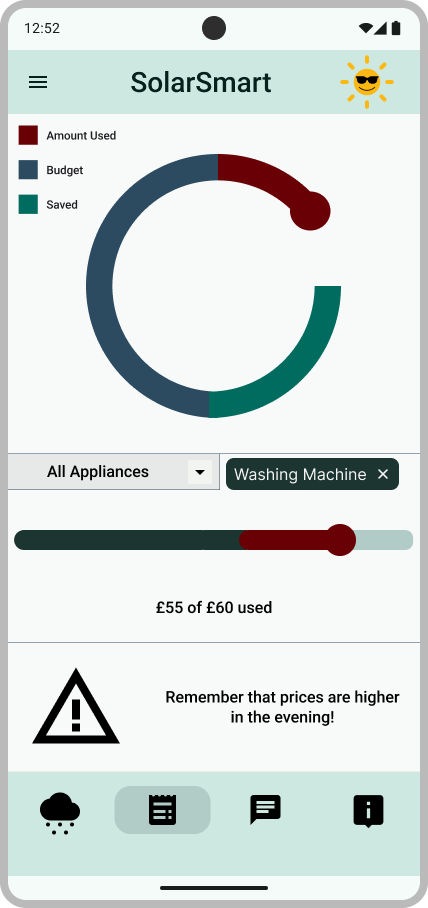

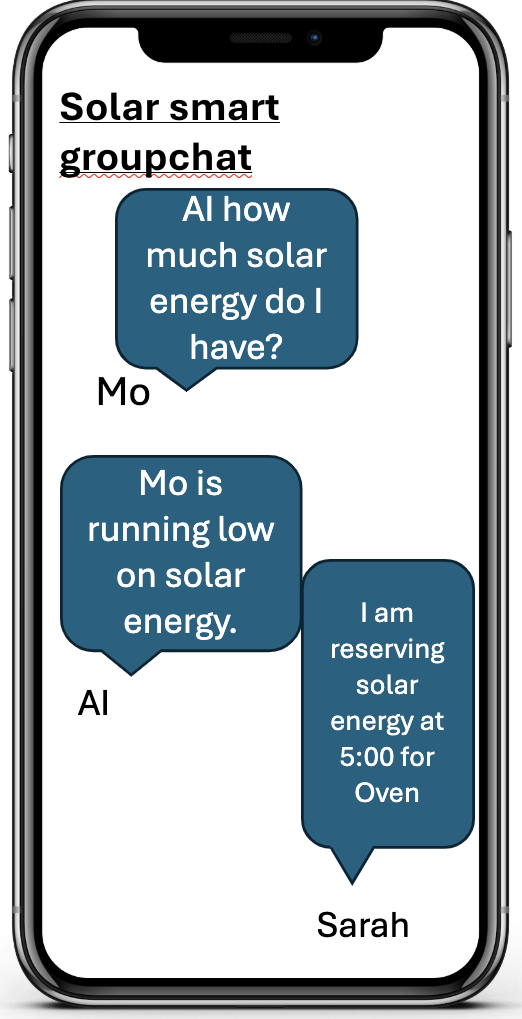

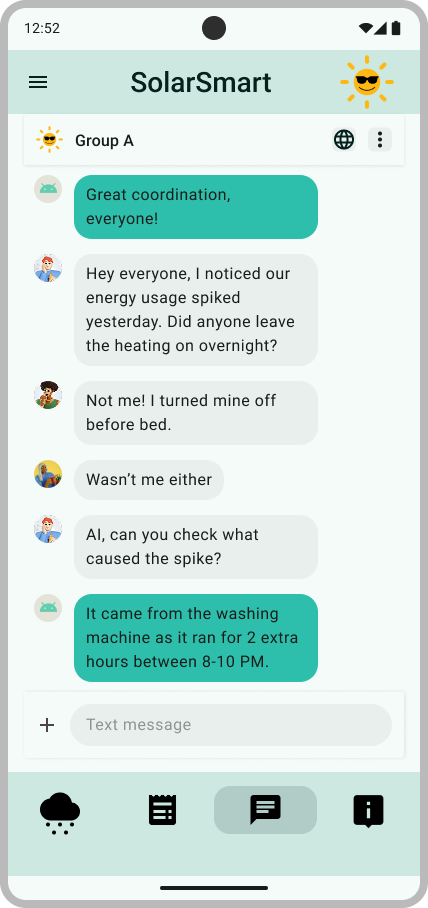

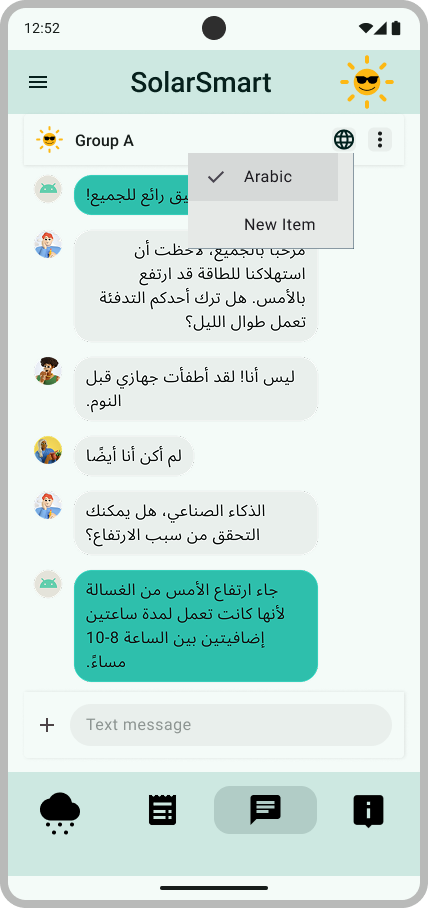

Group 2: SolarSmart

The second group presented an app which placed a strong emphasis on data visualisation. They sketched a chart designed to convey key energy information to users, with the ability to filter this data by specific electrical appliances. Unlike other groups, who used paper and pen to prototype, this group used PowerPoint to sketch out their ideas.

They envisioned AI as a conversation facilitator within a group chat feature. Notably, they highlighted the importance of translation tools during the workshop, especially to support individuals who might not speak English fluently.

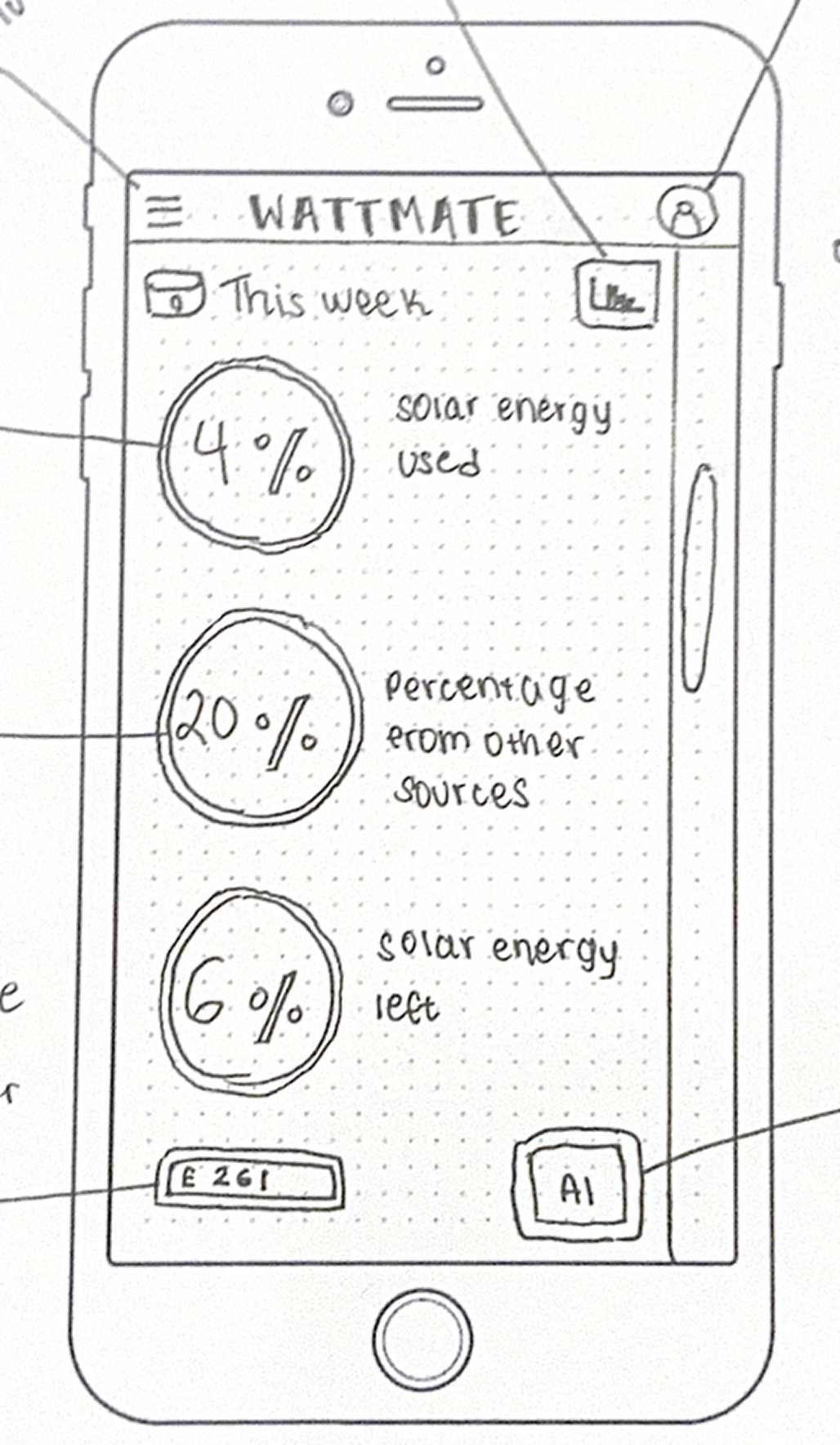

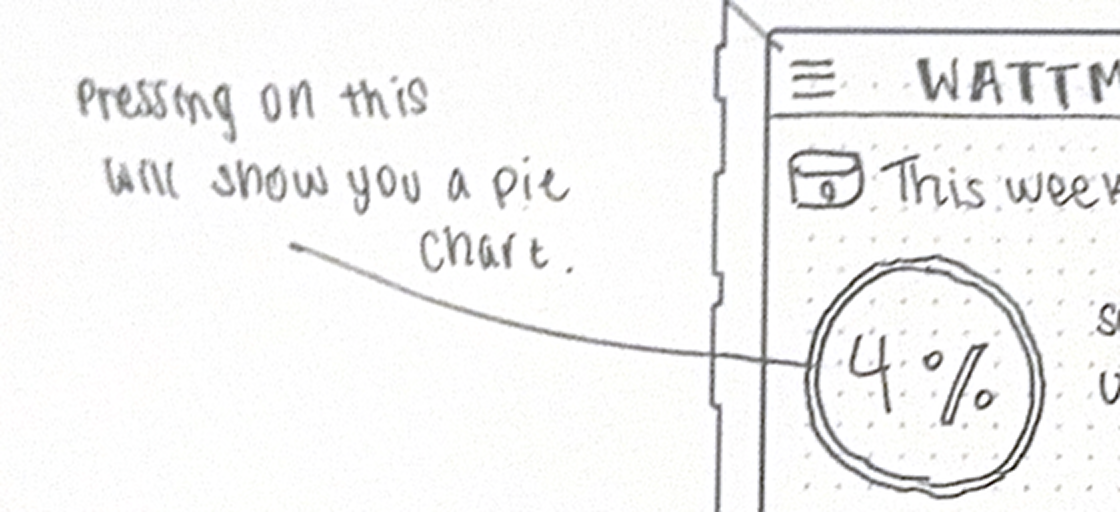

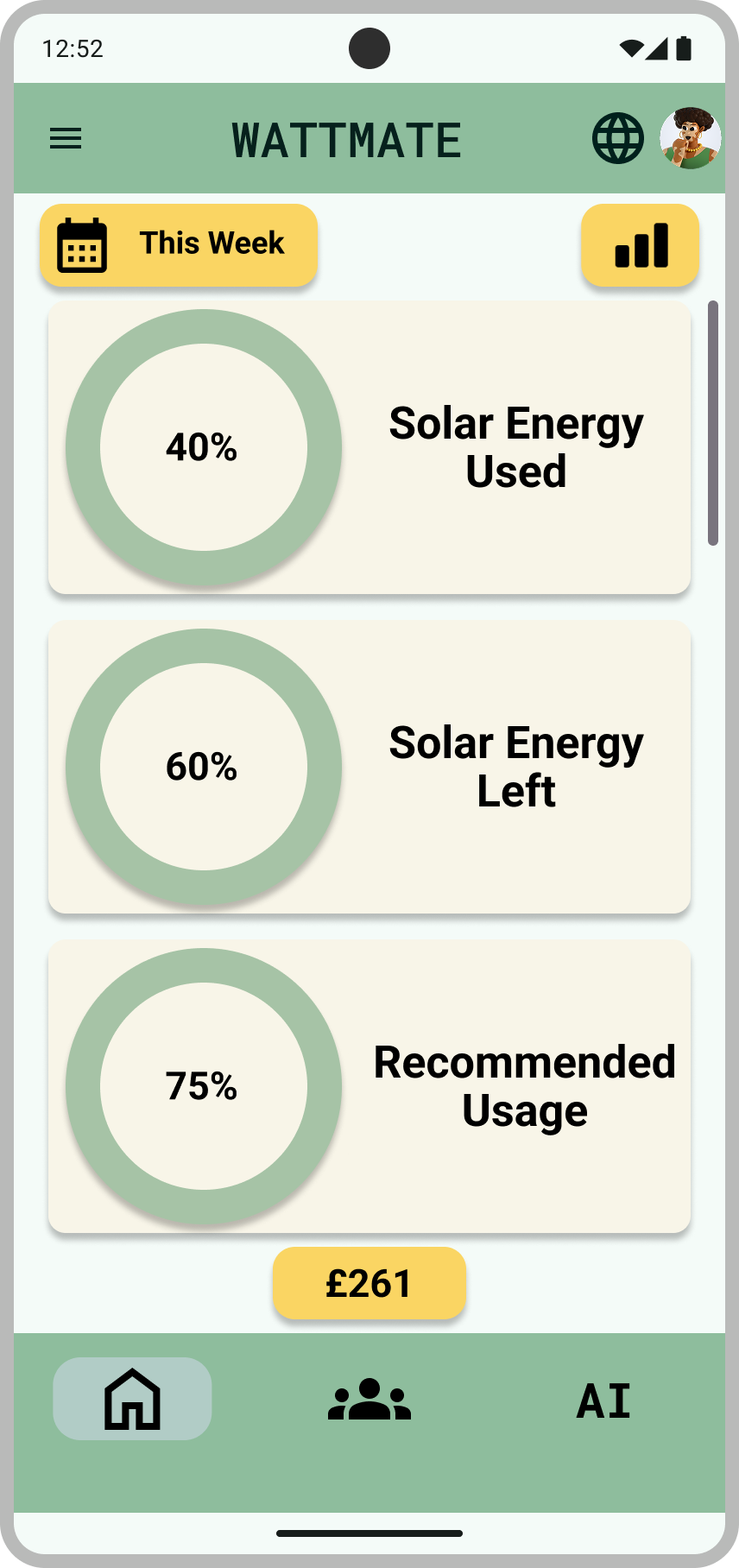

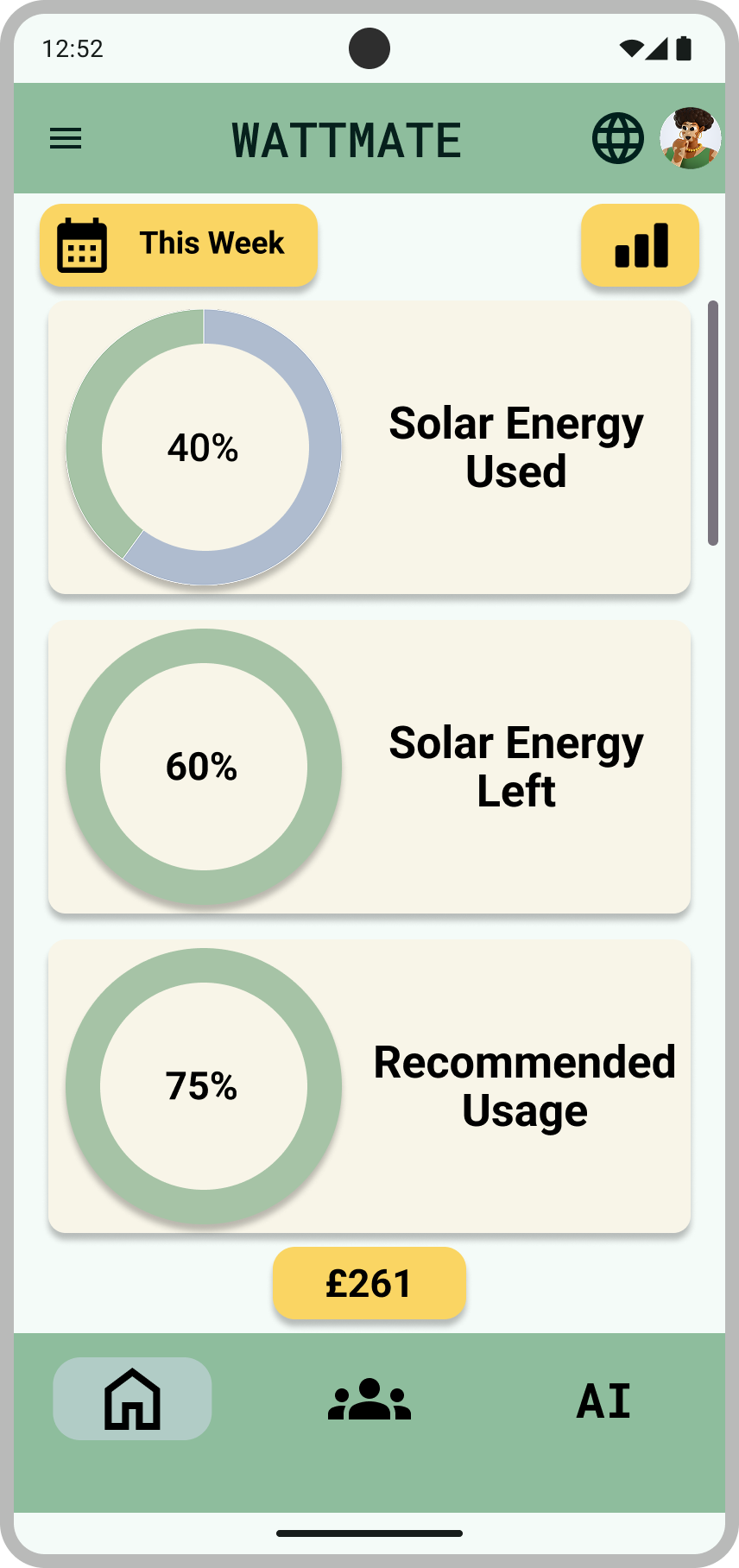

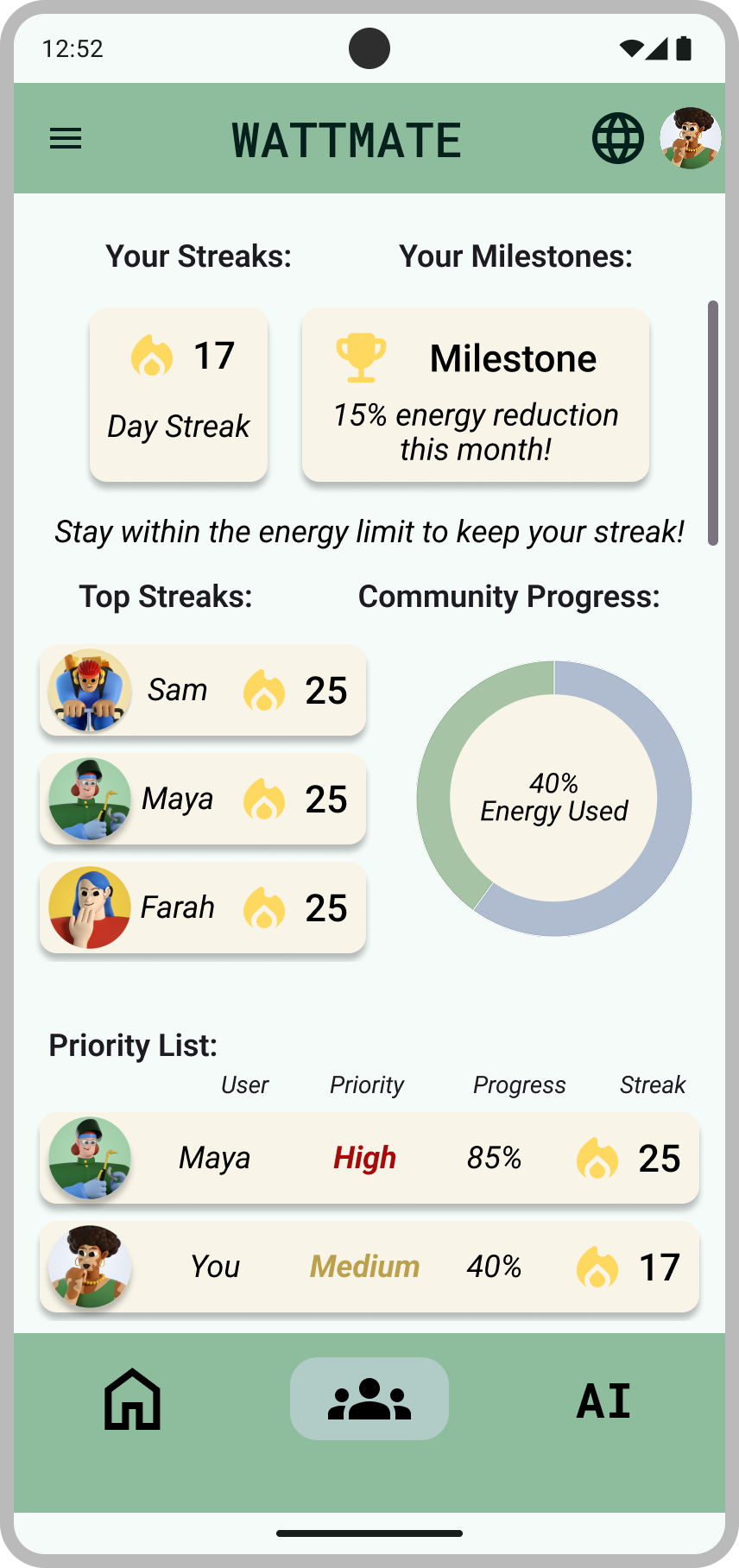

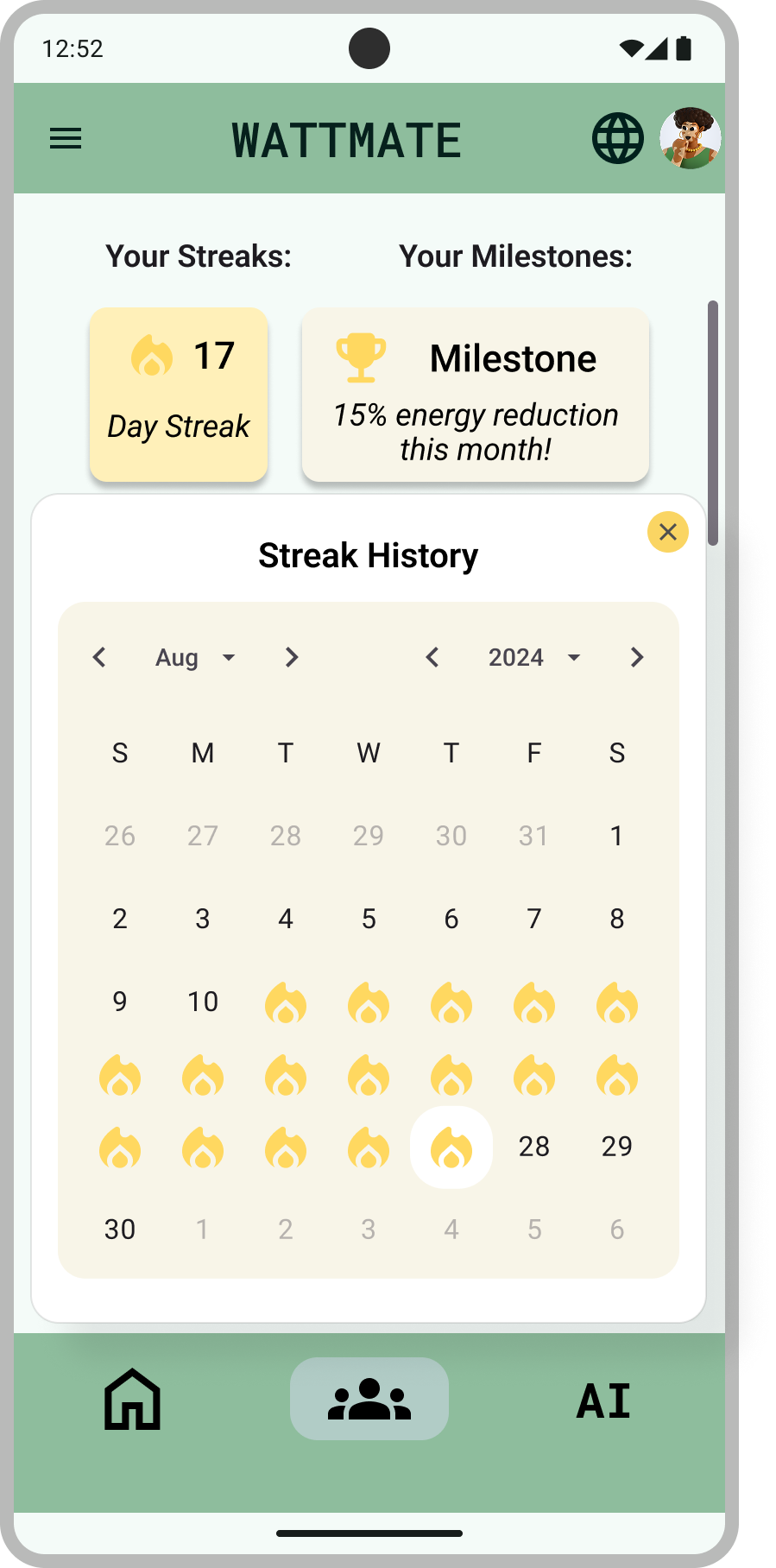

Group 3: WattMate

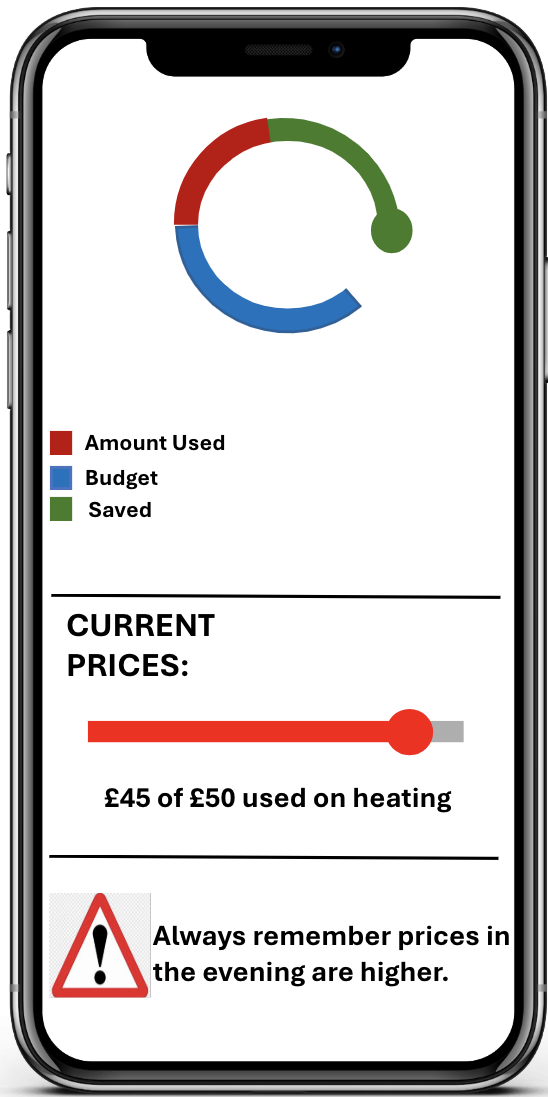

The third group introduced an app which also focused on visualisations, but approached it by creating separate visualisations for different metrics.

They incorporated the concept of streaks to encourage consistent, responsible energy usage or staying within a set budget.

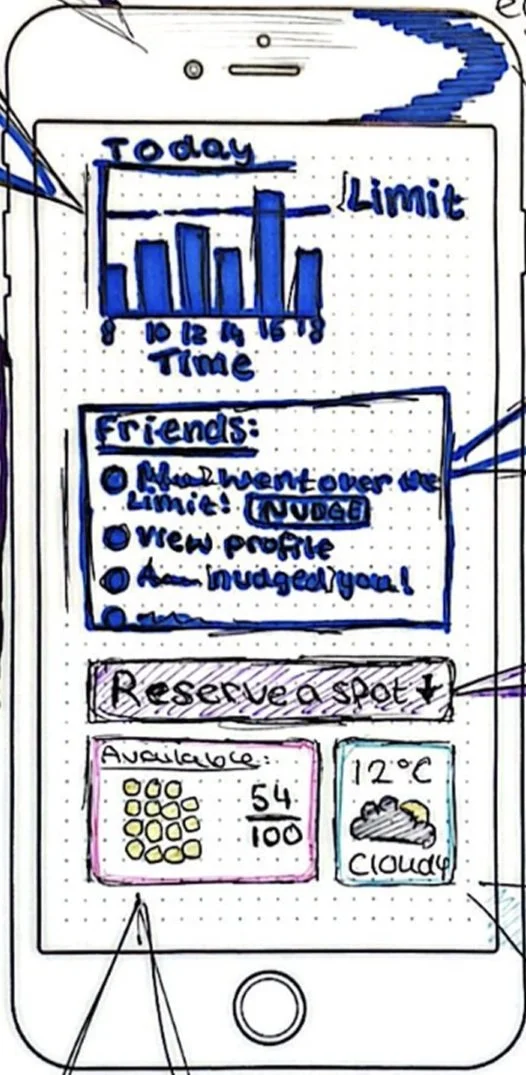

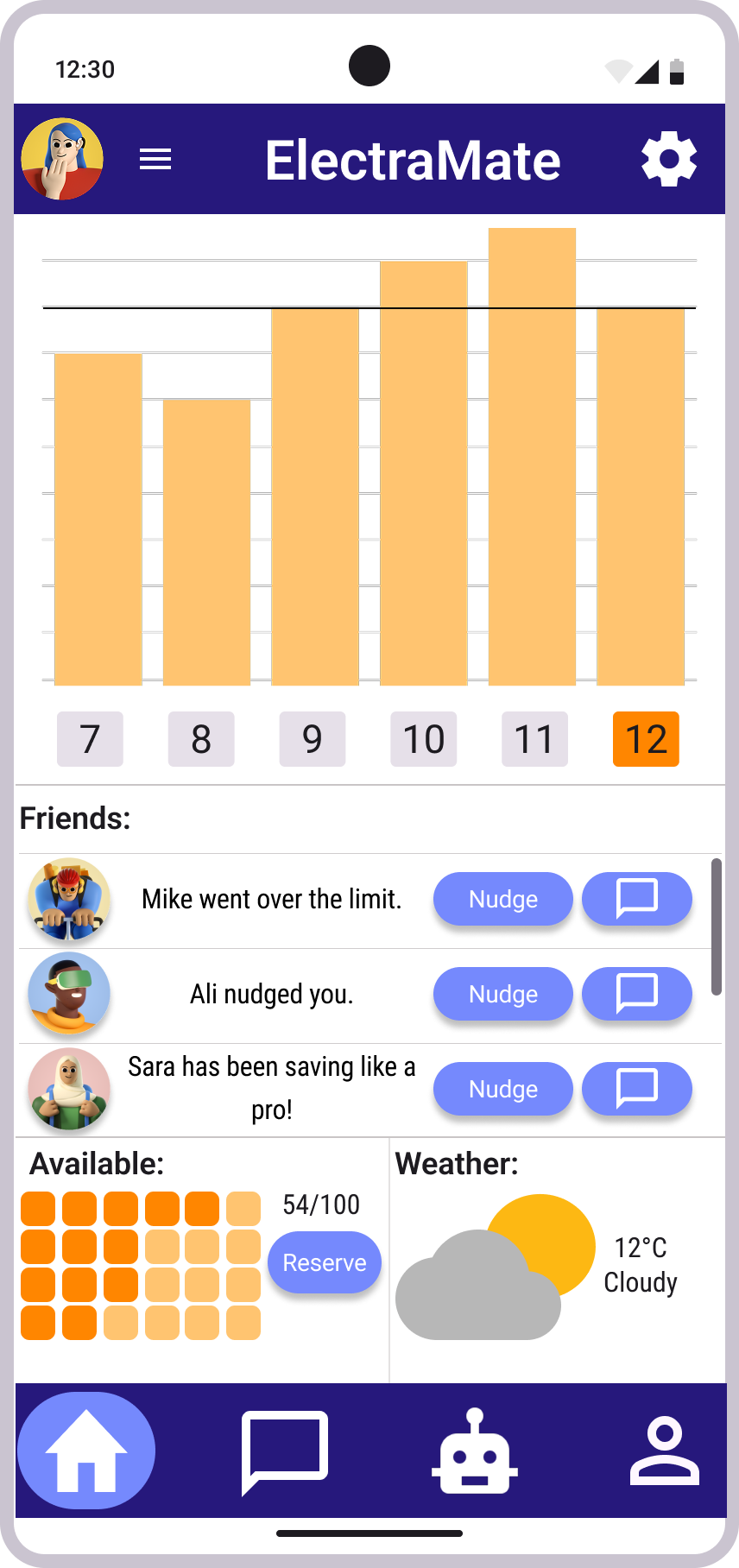

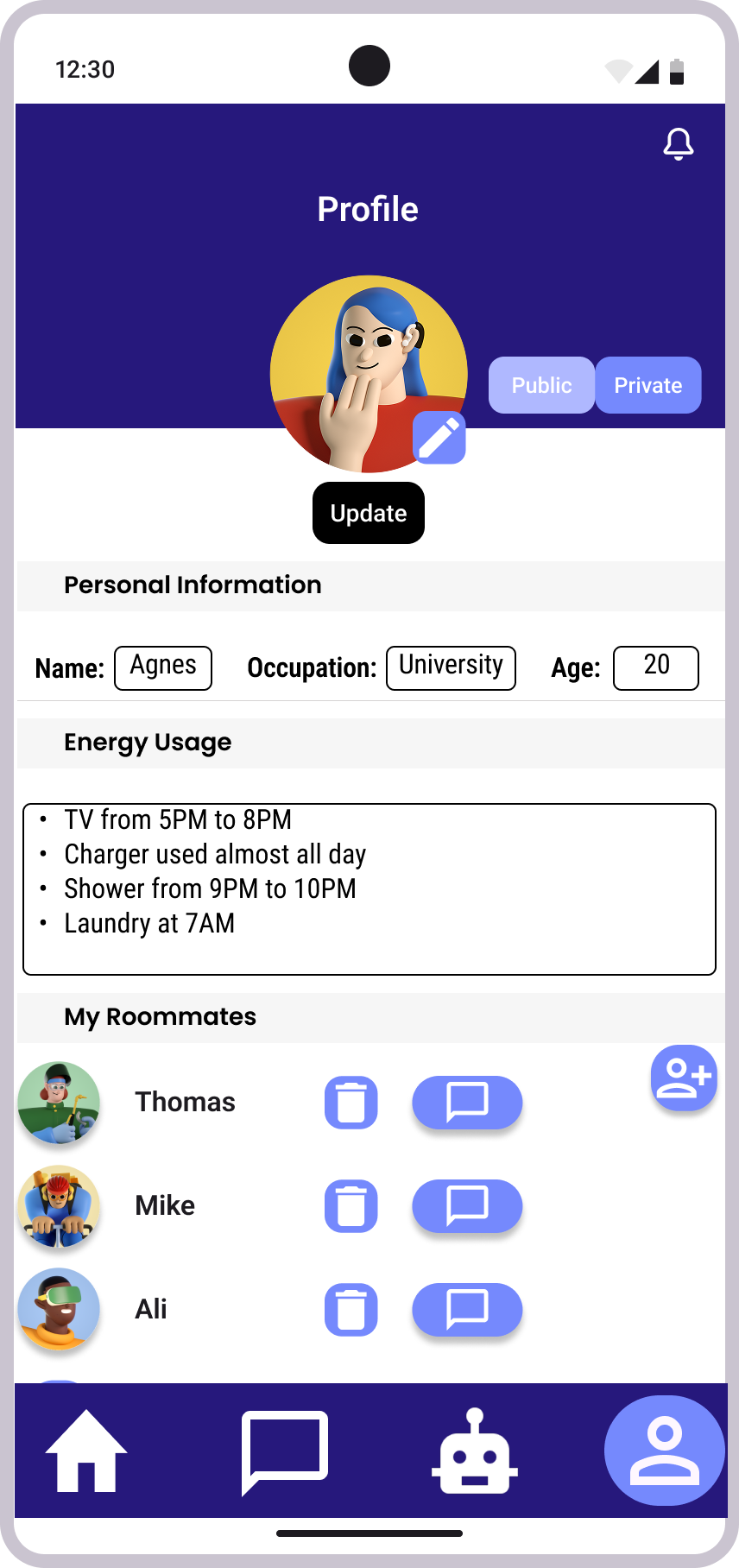

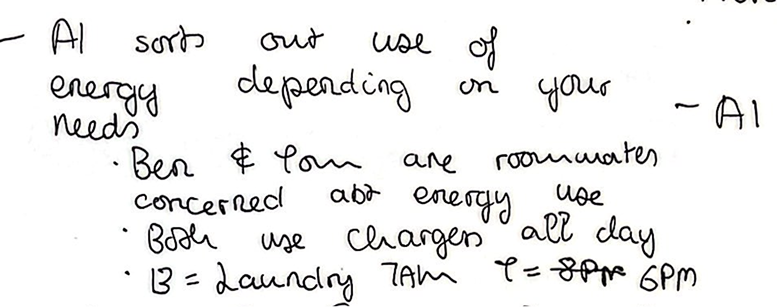

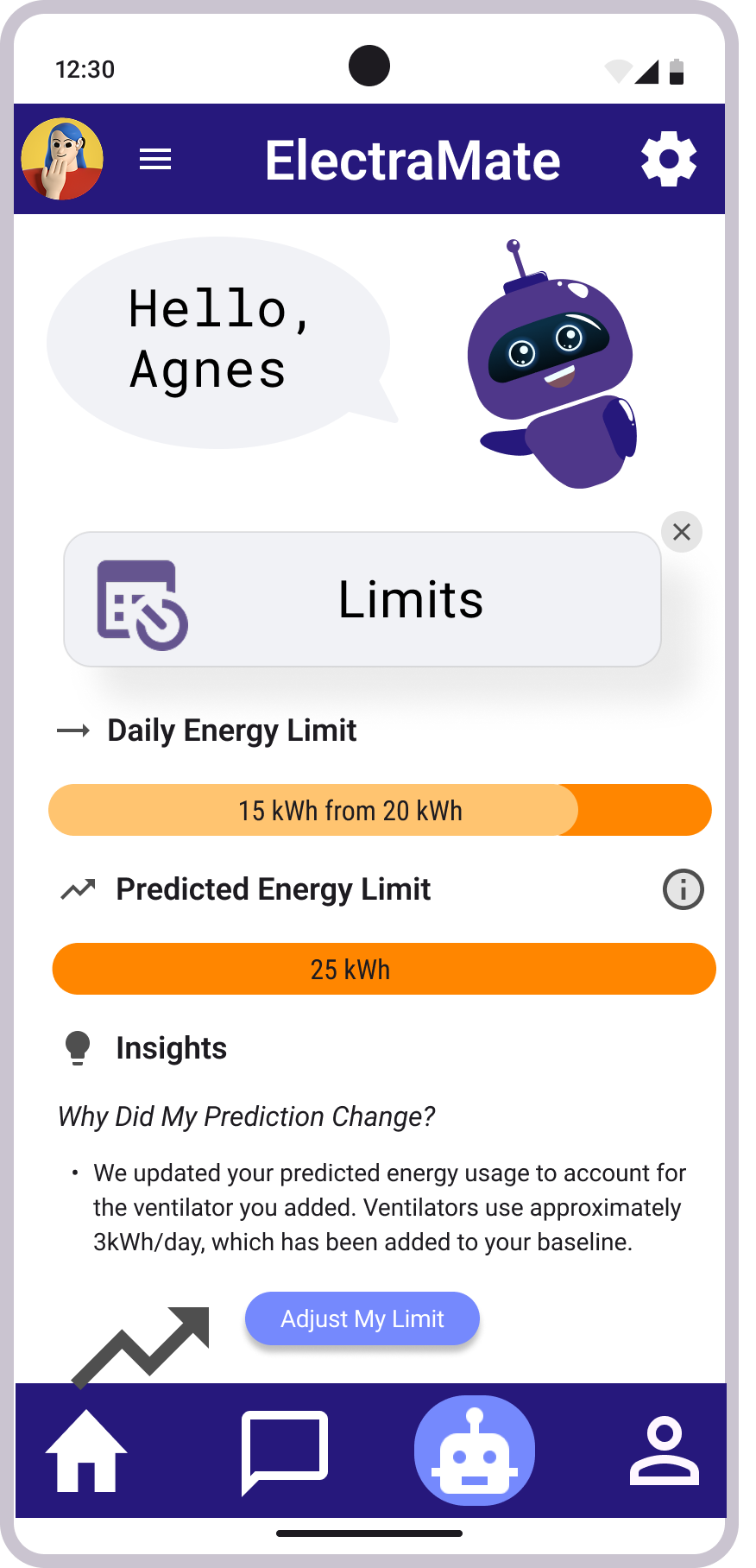

Group 4: ElectraMate

The fourth group designed an app featuring a unique communication method through nudges in a Friends feed.

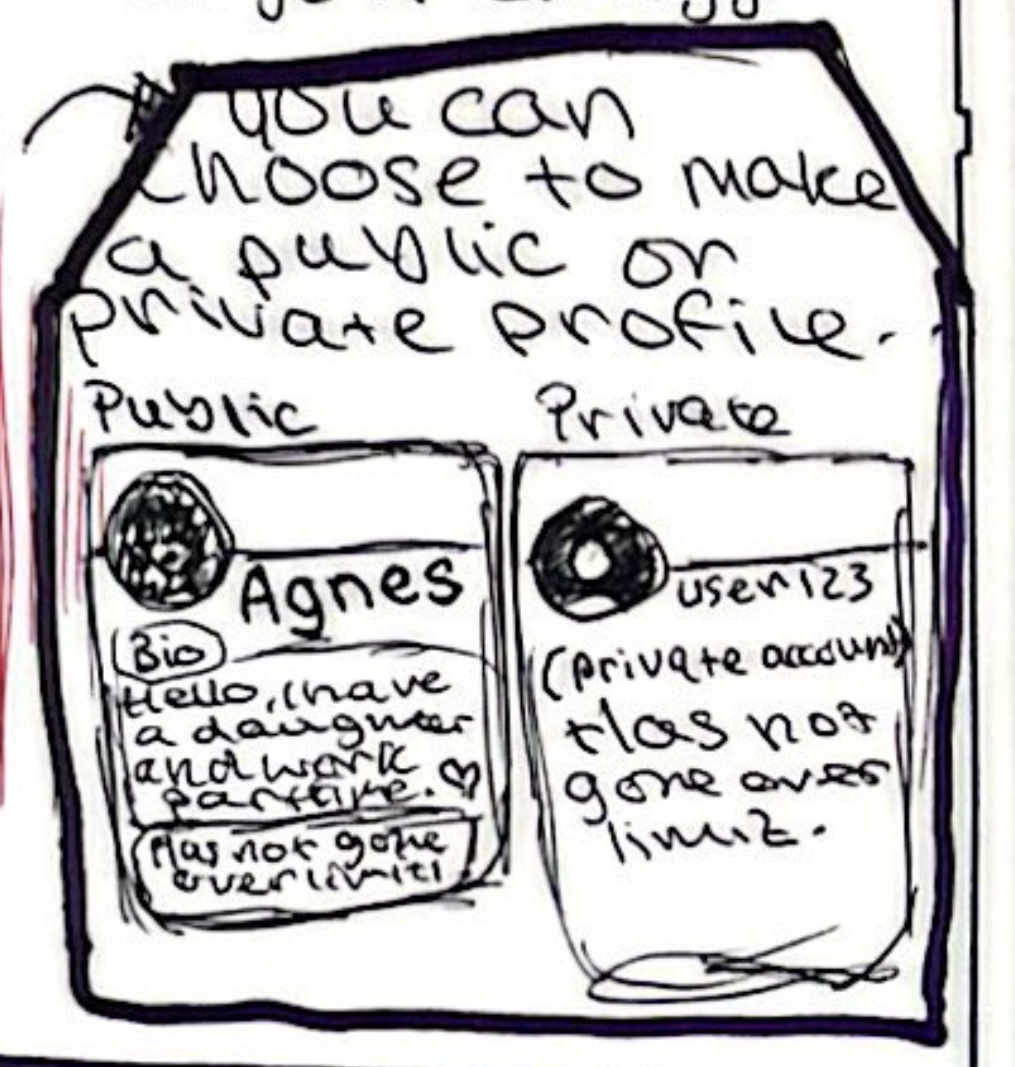

They placed importance on user privacy, proposing that profiles could be set as either public or private.

Their concept of AI was one that allocates energy based on users’ needs and continuously updates predictions accordingly.

Pitching to a Panel

In the final stage, the students pitched their app ideas to a panel of judges that included professionals from academia as well as representatives from the local council. They received constructive feedback on their designs, giving them a sense of how their ideas might be received in real-world contexts.

Reflection

This project stood out to me because it offered a refreshing shift in the typical design dynamic. Rather than conducting traditional user research myself, I took on the role of the sole UX designer, while the students effectively became the researchers. They identified the goals, values, and features they found most meaningful and communicated them through their sketches and discussions. My responsibility was to take those ideas and translate them into more polished, presentable designs, without overriding their core intentions. This required me to practice restraint as a designer, ensuring that my interpretations remained true to their vision. It was a humbling and rewarding exercise in participatory design.

Working directly with students also highlighted the importance of involving young people in shaping systems they will likely engage with in the future. As future users and potentially even designers of such energy coordination tools, their perspectives are invaluable. Their ideas highlighted concerns that might not always surface in adult-led design processes.

While many of their concepts revolved around mobile apps, which were intuitive and accessible starting points for them, we might have expanded their thinking by introducing alternative tools and technologies, such as smart meters, home displays, or even tangible interaction methods. Doing so could have encouraged a broader exploration of how energy coordination might happen beyond screens. In future iterations, I’d like to see how combining creative storytelling with exposure to real-world technologies might deepen the students' understanding and lead to even more inventive solutions.